Future Directions

Contents

Future Directions¶

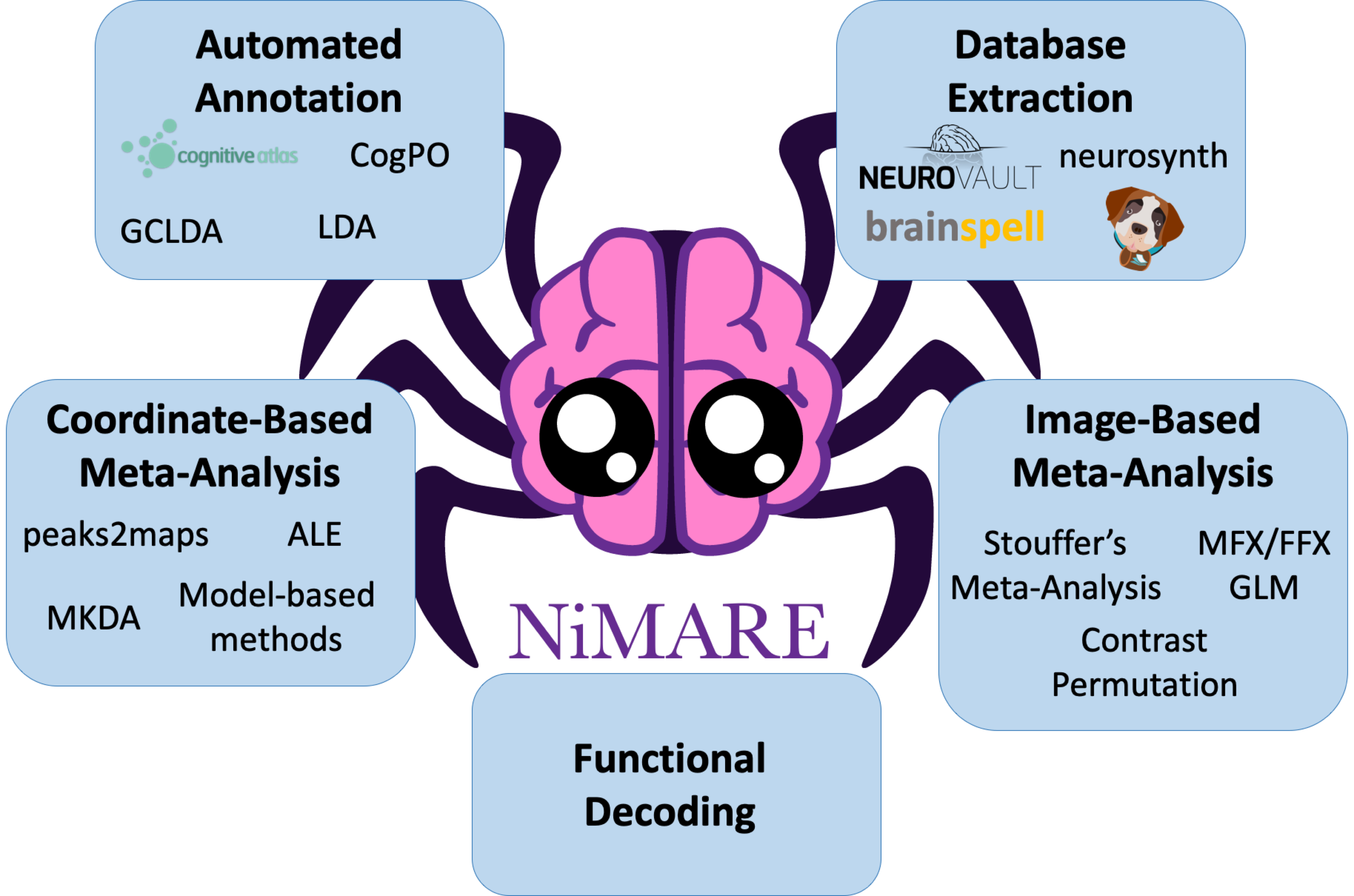

NiMARE’s mission statement encompasses a range of tools that have not yet been implemented in the package. In the future, we plan to incorporate a number of additional methods. Here we briefly describe several of these tools.

Integration with external databases¶

A resource which may ultimately be integrated with Neurosynth is Brainspell. Brainspell is a port of the Neurosynth database in which users may manually annotate the automatically extracted study information. The goal of Brainspell is to crowdsource annotation through both expert and nonexpert annotators, which would address the primary weaknesses of BrainMap (i.e., slow growth) and Neurosynth (i.e., noise in data extraction and annotation). Annotations in Brainspell may use labels from the Cognitive Paradigm Ontology (CogPO) [Turner and Laird, 2012], an ontology adapted from the BrainMap Taxonomy, or from the Cognitive Atlas [Poldrack et al., 2011], a collaboratively generated ontology built by contributions from experts across the field of cognitive science. Users may also correct the coordinates extracted by Neurosynth, which may suffer from extraction errors, and may add important metadata like the number of subjects associated with each comparison in each study.

Brainspell has suffered from low growth, which is why its annotations have not been integrated back into Neurosynth, but a new frontend tool for Brainspell, geared toward meta-analysts, has been developed called metaCurious. MetaCurious facilitates neuroimaging meta-analyses by allowing users to iteratively perform literature searches and to annotate rejected articles with reasons for exclusion. In addition to these features, metaCurious users can annotate studies with the same labels and metadata as Brainspell, but with the features geared toward meta-analysts site usage is expected to exceed that of Brainspell proper.

While NiMARE does not natively include tools for interacting with Brainspell or metaCurious, there are plans to support NiMARE-format exports in both services.

Seed-based D-Mapping¶

Seed-based d-mapping (SDM) [Radua et al., 2012], previously known as signed differential mapping, is a relatively recently-developed approach designed to incorporate both peak-specific effect size estimates and unthresholded images, when available. In SDM, foci are convolved with an anisotropic kernel which, unlike the Gaussian and spherical kernels employed in ALE and MKDA, respectively, accounts for tissue type to provide more empirically realistic spatial models of the clusters from the original studies. The SDM algorithm is not yet supported in NiMARE, given the difficulty in implementing an algorithm without access to code.

Model-based CBMA¶

Model-based algorithms, a recent alternative to kernel-based approaches, model foci from studies as the products of stochastic models sampling some underlying distribution. Some of these methods include the Bayesian hierarchical independent cluster process model (BHICP) [Kang et al., 2011], the Bayesian spatially adaptive binary regression model (SBR) [Yue et al., 2012], the hierarchical Poisson/Gamma random field model (HPGRF/BHPGM) [Kang et al., 2014], the spatial Bayesian latent factor regression model (SBLFRM) [Montagna et al., 2018], and the random effects log Gaussian Cox process model (RFX-LGCP) [Samartsidis et al., 2019].

Although these methods are much more computationally intensive than kernel-based algorithms, they provide information that kernel-based methods cannot, such as spatial confidence intervals, effect size estimate confidence intervals, and the facilitation of reverse inference. A more thorough description of the relative strengths of model-based algorithms is presented in Samartsidis et al. [2017], but these benefits, at the cost of computational efficiency, have led the authors to recommend kernel-based methods for exploratory analysis and model-based methods for confirmatory analysis.

NiMARE does not currently implement any model-based CBMA algorithms, although there are plans to include at least one in the future.

Additional automated annotation methods¶

Several papers have used article text to automatically annotate meta-analytic databases with a range of methods. Alhazmi et al. [2018] used a combination of correspondence analysis and clustering to identify subdomains in the cognitive neuroscience literature from Neurosynth text. Monti et al. [2016] generated word and document embeddings in vector space from Neurosynth abstracts using deep Boltzmann machines, which allowed them to cluster words based on semantic similarity or to describe Neurosynth articles in terms of these word clusters. Nunes [2018] used article abstracts from Neurosynth to represent documents as dense vectors as well. These document vectors were then used in conjunction with corresponding coordinates to cluster words into categories, essentially annotating Neurosynth articles according to a new “ontology” based on both abstract text and coordinates.

Meta-analytic databases may also be used in conjunction with existing ontologies in order to redefine mental states or to refine the ontology. For example, Yeo et al. [2016] used the Author-Topic model to identify connections between Paradigm Classes (i.e., tasks) and Behavioral Domains (i.e., mental states) from the BrainMap Taxonomy using the BrainMap database. Other examples include using meta-analytic clustering, combined with functional decoding, to identify groups of terms/labels that co-occur in neuroimaging data, in order to determine if the divisions currently employed in existing ontologies accurately reflect how mental states are separated in the mind (e.g., [Laird et al., 2015, Riedel et al., 2018, Bottenhorn et al., 2019]).